|

|

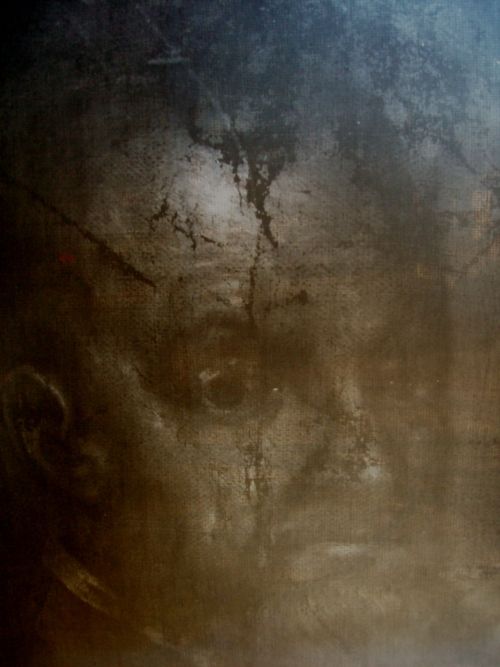

Titian (attributed), Portrait of

Venetian Official, late 1510s - early 1520s, 45cm x 60cm, oil on canvas, price on request

The Portrait

of Venetian Official Based on painting materials, especially the ground, the Portrait of the Venetian Official has to be attributed into the early sixteenth century. The painting is executed in the style typical for the Sixteenth Century Venetian art. However, in the first decades of the century, the majority of Venetian artists still worked in the fifteenth century 'fine brushstroke' style. There were only three innovator- artists who are known to introduce the new oil painting techniques in the early decades of the sixteenth century, Giorgione, Titian and Sebastiano. Sebastiano painted more contour oriented than the author of the Portrait of the Venetian Official. The Venetian Official is executed in the masterly manner with bold, clearly visible brushstrokes, with the glazes creating the broken tone, which would indicate Titian’s art. Only the lead white parts are executed in bravura relief technique, which are characteristics of early Titian’s technique. Therefore, it is appealing to suggest that Portrait of the Venetian Official was painted by Titian in late 1510s-early 1520s. It is clearly a fast painted commercial portrait created to satisfy the customer. However, there are no other commercial portraits of Venetian officials painted by Titian on this early stage of his career known to survive.  Figure 1. Titian (attributed), Portrait of Venetian Official The Portrait

of the Venetian Official [Fig.1] is an example demonstrating the difficulties

in search for the definite attribution of the undocumented paintings. The Portrait

of the Venetian Official, probably a senator or procurator,

is one of the undocumented artworks. The research of modern data registries and old sources did not provide any information.

According to the former owner, an old lady related to German nobility, the portrait belonged to the family for a long time,

more than hundred years. She kept this unframed dark picture in the closet of her Berlin home among other dark pictures and

damaged artifacts. In late 1970s, by cleaning and reducing the household, she gave this painting as part of the payment for

the household services to another lady, whose grandson, an artist and collector, was interested in old canvases. The picture

was so dark and dirty that any identification was very difficult.In 1992-93, the Venetian

Official was cleaned, restored and x-rayed. The cleaning exposed the

painting in early Titian style, some damages and overpaintings. The original canvas is attached to another hand-woven canvas.

The picture was apparently reduced in size and stretched on the newer, probably nineteenth century stretchers. [Fig.2 and

3]

Due to the

overall impression, the painting was estimated as sixteenth century Venetian artwork. The cleaning also revealed that during

one of the previous restoration attempts, a few parts of the original painting surface were destroyed and scratched revealing

white gesso ground. On the x-radiograph, these parts look completely dark which indicates the absence of lead white

in the ground layer [Fig.4]. Since the middle of the sixteenth century, the toned undergrounds and broader usage of lead white

became more or less the norm.[i] In 1568, Vasari also suggested to use a lead white mix instead of traditional

gesso, to make paintings less brittle.[ii] The Artists north of the Alps began to apply lead white grounds much earlier.

Though Titian continued to use traditional gesso through out his career, since middle of the century, he began to add warm,

medium-gray coating and selectively used colored underpainting.[iii] Therefore, paint layers applied directly on the white thick lead-free gesso indicate that the picture was created in

the first decades of the sixteenth century or even earlier.

After

the cleaning, the visible scratches of the gesso became apparent at the left eye of the Venetian

Official. The gesso was scratched one to half millimeter deep without damaging or exposing the canvas. Such relatively

thick white gesso was normally applied by the Venetian artists in the last quarter of the fifteenth, early sixteenth century.[iv] Through the sixteenth century, the Venetian artists continue to minimize

the thickness of the ground. Since ca. middle of the sixteenth century, the ground of Venetian paintings became so extremely

thin that it barely filled the deeper parts of the canvas mesh.[v] Some middle to late sixteenth century Venetian canvases had no gesso at all.[vi] The unfortunate old damages of the Venetian

Official painting surface allowed the deep inside into the ground layer,

which helps to identify the age of the artwork as probably early cinquecento artwork. Despite the relatively thick ground, the canvas texture of the Venetian

Official is visible through the painting surface [Fig.5 and 6], which

is a characteristic of Venetian art since the late fifteenth century. As David Rosand noted, “Already in the final years

of the fifteenth century, Carpaccio had thinned the gesso priming to the canvas, thereby revealing more of the texture of

the cloth.”[vii] Since early sixteenth century, Venetians were developing a new painting technique,

increasingly incorporating the visible brushstroke and canvas texture into their painting style. Rosand formulated this by

Giorgione pioneered technique as, “the actual texture of paint, the physical substance of the medium articulated in

its reciprocal relation to the canvas ground.”[viii] The thinner ground layer had double advantage. The painting surface became

less brittle and the visible canvas texture added an additional artistic effect. Very thin gesso ground covered with the colored

primer and often additional imprimatura became

more or less a norm for the Venetian painters in the second half of the sixteenth century.  Figure 5. Figure 5.  Figure 6. (photographs in raking light) Figure 6. (photographs in raking light)Therefore, the thickness of the

ground, visible canvas structure, missing of white lead containing primer and missing primavetura in the Portrait of the Venetian

Official allow us to suggest the date of the creation into the first

decades of the sixteenth century. The fact that despite chalk gesso, the colors still sustain their brilliance may be explained

by the tempera-oil mix of the primary paint layers, tempera grassa.[ix] In 2009, the Portrait of the Venetian Official was examined in the conservation lab of Chrysler Museum of Arts, Norfolk.

The picture was studied with implementation of ultraviolet and infrared lights. The examination confirmed the results of the

1992 examination that the painting is an authentic Venetian artwork. According to the museum’s conservator, Mark Lewis,

“The painting exhibits the type of materials, paint cracking and signs of age typical for 16th-17th c work. The painting is in fairly stable condition for its age but shows significant

loss and wear. Extensive retouching is also visible.”[x] Lewis examined the picture in the condition after the 1992-93 restoration;

the exposed gesso parts were already retouched. The right side of the face of the Venetian

Official is in relatively good condition retaining the most of glazes,

while the left side of the face has more losses of the original paint. The background and robe are heavily retouched, while

the ermine-fur appears to be the original painting layer. The x-ray did not show any pentimenti.

According to the x-radiograph [Fig. 4], the original background was brighter and more sophisticated than the present monochrome

overpainting. However, the raking light indicated heavy losses of the original layers of the background and especially the

robe. Apparently, even some gesso ground under the robe was lost. Therefore, in 1992, it was decided not to remove overpaintings

of the background and robe. Summarizing his research results on old paintings, Belgian

expert-restorer Roger Marijnissen proposed the main guideline in investigating of the authorship of old artworks, “One

of the most important characteristics of the old masters is their economy of means: almost always the most rational means

available to the craftsman were chosen to achieve the objective.”[xi] The well preserved right side of the face of the Venetian Official reveals the original painting technique, demonstrating the “economy of means.”

The artist applied thick layer of paint directly on the gesso surface. The face is modeled with the few precise brushstrokes.

The impasto lead white brushstrokes on the brightest spots of the head are clearly visible. Especially visible are the lead

white impasto brushstrokes on the forehead, which function as the build-up of the head’s shape. Titian is credited to

be the first artist introducing such modeling methods.[xii] Analyzing the development of Titian’s bravura impasto brushstroke technique,

Laurie noted that Titian began in the early sixteenth century “by painting the highlights with white lead stiffly ground

and laid on in relief.” The Venetian Official exposes

exactly such painting technique. Fine green and red glazes were applied on top of the brighter

opaque paint layer, creating broken color, known as Titian’s “dirty color’ effect.[xiii] The details were modeled by glazes. On the x-radiograph of the Venetian

Official, the dark color marking the left side of the face has no clear defined contour separating it from the background;

all other contours are also soft. Linear contour drawing is not present. Such painting technique required the masterly virtuosity.

It was also an “economy of means”, than such image could be painted in a relatively short time. The master would

need only a few hours to complete such image, while the sitter was posing in the studio. After the master executed the image

and gave the basic tonality, the students and assistants were able to complete the costume and the background. Such painting

technique had double advantage: it not only allowed completing any portrait in a short time, it also demonstrated the master’s

virtuosity and made it difficult to imitate such technique which is based on the precise masterly brushstrokes and fine usage

of glazes. The x-radiography of Venetian

Official confirms that white lead was used to establish juxtapositions

of light and shadow and to mark the brighter parts in impasto relief, the technique which was pioneered by Titian. Alan Burroughs

concluded that Giorgione and Sebastiano, in contraire, carefully dispersed the paint. The clear defined contours are present

on the x-radiographs of their paintings.[xiv] However, x-radiography allows different interpretations, and therefore needs

additional confirmation of other research methods.[xv] Titian used white-lead to create light-shadow modulation, using his brush

freely disrespecting contours. He had no ready formula; the several x-radiographs of his artworks show that the handling of

primary bright, lead-white rich layer in the modeling of faces depended on the each individual light-shadow relationship in

each individual painting. Since Alan Burroughs published his investigation in late 1930s, many additional cinquecento paintings

were x-rayed.[xvi] The new x-radiographs show that Titian during his career continually

applied the impasto relief lead white on the forehead to model the head’s shape, while other sixteenth century artists

tended to apply the lead white only to mark the brightest spots. Titian’s painting technique was followed later by the

masters of the seventeenth century, most notably Rembrandt. David Rosand pointed

out that Giorgione also worked directly on the canvas, adjusting and changing his compositions, “brushing in his forms

without preliminary drawing.”[xvii] This innovation, the impasto and opaque oil color brushing technique introduced by Georgione and Titian was adapted

as the stylistic mark of the Venetian cinquecento art.[xviii] Other Venetian artists took over this technique. Therefore, the technique

itself does not necessary revile the authorship. Far more important is the quality of execution of the style, the area examined

by connoisseurs. Titian followers and imitators struggled to achieve the same effect in impasto and glazing like Titian.[xix] Their glazes often appear as sharp colorful hues, in contrast to Titian’s

broken neutral tones achieved by applying glazes contrasting the tonality of the opaque underlayer.[xx] Rosand noted that “The portraits by workshop assistants and Titian

imitators tended to be tentative and bland.” [xxi] Though not “tentative and bland”, the Venetian

Official still differs

from the known Titian portraits created in this period. It is mainly the format of the composition. Early in his career, Titian introduced a new portrait format, which became a standard during the

sixteenth century. It is a three-quarter with hands visible. Such format allowed to achieve additional expression using the

dynamic of pose and gesture, as well as the juxtaposition of materiality of cloth and flesh.[xxii] The head of the sitter was normally painted in the original size, therefore

the size of the entire picture was dictated by this proportion. Such portraits are normally in average 100cm x 80cm, differing

from each other by 10-20cm. The Portrait of the Venetian

Official is reduced in size horizontally on both sides and vertically

at the bottom edge, which is indicated by the painted edges overlapped over the support. The head of the Venetian official

is rendered in the original size, ca. 26cm, while the entire reduced size of the canvas is only 60cm x 45cm.. Such reduction

of the shoulders and body does not allow any analysis of the pose and gesture, while the condition of the red robe makes it

almost impossible to analyze the painting style of the cloth. Therefore, the analyses of the Venetian

Official had to be reduced to the portraiture itself.  Figure 7. Figure 7.The Venetian Official is

a bust portrait of a bearded man [Fig.7 and 8]. His body is turned slightly to the left, while his head is turned to the right.

His gaze is introspective and energetic at the same time, while his thin lips do not reveal any emotions. It is clearly a

representative portrait of a strong and energetic leader. But his gaze is also to some extend contemplative. Such representative

portrayal differs from the idealized introspective contemplative mood of the portraits by Giorgione. Lino Moretti suggests that melancholic contemplative mood of Giorgione’s artworks was fashionable

in Venetia a short period after the disastrous defeat of Agnadello in 1509.[xxiii] However, David Allan Brown implies that, “Though the romantic aura of Giorgione’s portraits doubtless reflects

his own sensibility, the poetic conceits they embody became clichéd through repetition.”[xxiv] The novelty of Titian portraits consisted in his talent to combine the representation of sitter’s individuality

and Georgionesque contemplativeness. Such combination of realistic and ideal aspects of human character reflected sixteenth

century humanist views.[xxv] The combination of vita

activa and vita contemplativa was also a quintessence of the ideal Venetian character in the late fifteenth and

sixteenth century.[xxvi] Therefore, it is not surprising that Titian was recognized very early in

his career as the leading portraitist of his century. Titian portraits do not just represent the character and social standing

of his sitter, but also the humanist aspects of the sixteenth century worldview. Antonio Paolucci noted, “The huge success

of Titian as a portrait painter in the high society of his time can be explained largely by his capacity to divine unerringly

and represent vividly the “ideal persona” of his sitter, without, however, distorting either the physical or the

psychological likeness of the personage.”[xxvii] In the sixteenth century Italy, “the ideal persona” was understood

as a person striving toward de duplici vivendi genere, the

combination of active live and contemplativeness. According to one

of the thinkers who influenced sixteenth century humanist ideas, Cristoforo Landino, only God unify active and contemplative

lives, but the humans can combine them, by involving in civic activities and taking time for contemplation.[xxviii] Landino also suggests that it is possible to be active and keep contemplative

mood at the same time. Such views were also endorsed by the Venetian humanists, Bernardo Bembo and Ermolao Barbaro.[xxix] Venetian humanist, Gasparo Contarini demonstrated the successful combination of meditations, theological studies and

active political service, and therefore was praised as the model of the Venetian virtues. Doge Alvise Mocenigo called him,

“the best gentleman this city has.”[xxx]  Figure 8. Figure 8.The representation of Venetian virtues, which

means the combination of active political or intellectual life with contemplativeness, was the important part of Titian portrayals.

Other Venetian artists, including Tintoretto and Veronese, also strived to represent sixteenth century humanist virtues. In

order to understand this important characteristic of Venetian renaissance portrayals, they should be compared to the portraits

by Moroni, which were also painted during the Cinquecento. As excellent portraitist, Moroni masterly rendered veristic, psychological

portrayals, but they do not show any idealistic contemplativeness. Such portrayals can be understood as the representation

of “intellectual skepticism” and therefore can be attributed to Mannerism.[xxxi] Giorgione and Moroni are two opposite poles of the sixteenth century culture; while Titian unites all cultural and

philosophical aspects of his time, showing in his portrayals sitter’s character and virtues as they were understood

in Italian cinquecento culture. In sixteenth century Venice, portraits of patricians had

a political function. Rona Goffen explains, “As the patricians increased in number so too did their commissions of portraits-

not only because there were more noble subjects to represent, but also as a function of heightened competition for positions

of power.”[xxxii] Therefore, for Venetian officials, it was a question of political importance and prestige to order their life-size

portraits by the recognized leading artists of the Venetian Republic: Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese.[xxxiii] The portraits of Venetian officials executed by less important artists

are mostly sixteenth, seventeenth century copies or imitations of the earlier painted portraits by the masters. Such artworks

are recognizable by the mediocre execution. In early sixteenth century, Giovanni Bellini, Cima and

Carpaccio, the Venetian artists, representing the late fifteenth century style, were still active and their art was popular.[xxxiv] However, already in the first decade of the sixteenth century, the

innovators Georgione, Titian and Sebastiano began to set a new trend in Venetian art. The pioneer of this new painting technique,

Giorgione died in 1510. His follower Sebastiano left Venice for Rome one year later. Giovanni Bellini died in 1516.As the

result, Titian became the leading artist in Venice.[xxxv] In 1533, Titian’s public status even increased from the recognized

leading Venetian artist to the knighted court artist of the Emperor Charles V. After such wide recognition in Europe, Titian

left primarily to others the privilege to create portraits of Venetian officials: procurators, magistrates, senators, ambassadors,

and sea captains.[xxxvi] In the second half of the sixteenth century, the majority of the portraits

of Venetian officials were created by Tintoretto.[xxxvii] Many of the paintings by Titian, his workshop and followers were destroyed

or dispersed around Europe. In estimate, eighty documented artworks by Titian are lost. How many undocumented original Titian

works exist? One of such undocumented, wrongly attributed portraits by Titian was recently discovered in the storage of the

National Gallery, London.[xxxviii] According to the estimates by Luba Freedman, there are 203 documented portraits

created by Titian.[xxxix] Based on the development stages of Titian’s style, she roughly

divided Titian’s oeuvre into three periods. From the first period 1506-36, one hundred eighty four paintings are documented;

sixty four of them are portraits.[xl] Herold Wethey lists for this period ca. thirty-two survived documented

and undocumented portraits from the overall total of 117 survived portraits painted during Titian’s lifetime.[xli] It means that approx. half of the documented portraits were lost. In

the last five hundred years, many archive documents were also lost or destroyed, therefore it is impossible to estimate how

many additional undocumented artworks by Titian exist in obscurity. Vasari

mentions that the portraits painted by Titian are so numerous that it would be impossible to record all of them. Probably

ironically, Vasari also implies that there has scarcely been a noble of high rank whose portrait has not been painted by Titian.

Carlo Ridolfi mentions several portraits of Venetian procurators in Procurator’s Rooms.[xlii] These portraits disappeared and are untraceable. Some of the artworks are

known to be destroyed by fire, but the fate of most of them is simply unknown. There are also several portraits painted by

Titian’s followers and imitators, which can be the copies after Titian. In addition, some of Titian’s original

artworks were completed or even overpainted by his students or other artists, which cause additional identification problems.

In many cases, the seventeenth and eighteenth century auction listings are the last documents indicating the fate of the artworks.

But these auction listings are often not detailed enough to make any positive identification. In addition, several original

inventory listings are lost or are incomplete. Therefore, in many cases, the identification of the artworks entirely depends

on the art historical analyzes. While the museum experts have all the modern investigation

methods, many private owners are often not able to recognize the origins of their paintings. In other cases, the hundreds

of years old pictures are in such poor condition that any positive identification appears to be almost impossible. However,

the news about discovery of previously unknown or misinterpreted Titian artworks appear regularly in the media. Such rediscoveries

may continue, because there are yet so many artworks which disappeared for a long time in obscurity. The recently discovered Portrait of the Venetian Official appears

to be one of such artworks. [@

text and photo credits: Frost Art Gallery, www.frostpublishing.net] [i] Robert Wald, “Materials and Techniques of Painters in Sixteenth-Century

Venice”, Frederick Ilchman et el., Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese

Rivals in Renaissance Venice. (Boston: MFA Publications, 2009), 75-76. [ii] Robert Wald, “Materials and Technique of Painters in Sixteenth-Century

Venice”, in Frederick Ilchman et.el., Titian, Tintoretto,

Veronese Rivals in Renaissance Venice, (Boston: MFA Publications, 2009),

76. [iii] Robert Wald, “Materials and Technique of Painters in Sixteenth-Century

Venice”, 76. [iv] Gilberte Emile-Male, The

Restorer’s Handbook of Easel Painting, (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1976), 41. [v] Pim W.F. Brinkman, “Technical Investigation”, Anton W.A. Boschloo

and Gert Jan J. van der Sman, tr. Mandy Sikkens, Italian Paintings from

the Sixteenth Century in Dutch Public Collections, (Florence: Centro

Di, 1993), 137. Brinkman investigated Venetian paintings created ca. 1540 until the end of the century.[vi] See Pim W.F. Brinkman, “Technical Investigation”, Ibd. [vii] David Rosand, Painting

in Cinquecento Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, (New Haven: Yale

Univ.Press, 1982), 20. [viii] David Rosand, Painting

in Cinquecento Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, 18-19. [ix] Max Doerner, The Materials

of the Artist and their use in Painting with Notes on the Technique of the Old Masters, (New

York: Harcourt, 1934), 347 [x] Lewis, ChryslerMuseum of Arts, “Condition Report”, 2009. [xi] R.H. Marijnissen, Paintings,

Genuine, Fraud, Fake, Modern methods of examining paintings, (Brussels:

Elsevier, 1985), 199. [xii] A.P. Laurie, The Technique

of the Great Painters, (London: Carroll and Nicholson, 1959), 125. [xiii] Max Doerner, The Materials

of the Artist and their use in Painting with Notes on the Technique of the Old Masters, (New

York: Harcourt, 1934), 347 [xiv] e Elke Oberthaler and Elizabeth Walmsley, “Technical Studies of Painting

Methods”, David Alan Brown et el., Bellini, Giorgione, Titian and

the Renaissance of Venetian Painting, (Washington, DC: National Gallery

of Art in association with New Haven: Yale Univ Press, 2006), 286-300. [xv] Elke Oberthaler and Elizabeth Walmsley, “Technical Studies of Painting

Methods”, 298. [xvi] See newly published x-radiographies in Susanna Biadene ed., Titian

Prince of Painters, (Venice: Marsilio Editori, 1990). [xvii] David Rosand, Painting

in Cinquecento Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, (New Haven Yale University Press, 1982), 20. [xviii] David Rosand, Painting

in Cinquecento Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, 21. [xix] Max Doerner, The Materials

of the Artist and their use in Painting with Notes on the Technique of the Old Masters, (New

York: Harcourt, 1934), 346-47 [xx] Max Doerner, The Materials

of the Artist and their use in Painting with Notes on the Technique of the Old Masters, 346. [xxi] David Rosand, Painting

in Cinquecento Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, (New Haven: Yale

Univ.Press, 1982), 208. [xxii] David Alan Brown, “Portraits of Men”, Bellini,

Giorgione, Titian and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting, (Washington,

DC: National Gallery of Art in association with New Haven: Yale Univ Press, 2006), 243. [xxiii] Lino Moretti, “Portraits”, eds. Jane Martineau and Charles Hope, The Genius of Venice 1500-1600, (New

York: Abrams, 1984), 32. [xxiv] David Alan Brown, “Portraits of Men”, Bellini,

Giorgione, Titian and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting, (Washington,

DC: National Gallery of Art in association with New Haven: Yale Univ Press, 2006), 243. [xxv] See Richard Douglas, “Talent and Vocation in Humanist and Protestant

Thought”, and Felix Gilbert, “Religion and Politics in the Thought of Gasparo Contarini”, eds. Theodore

K. Rabb and Jerrold E. Siegel, Action and Conviction in Early Modern Europe, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969).[xxvi] Oliver Logan, Culture

and Society in Venice 1470-1790, (New York: Scribner, 1972), 50.The fifteenth-sixteenth century discussion on “vita activa”

and “vita contemplative” is extensively researched, there are many publications on this subject. The interpretation

of the philosophy of Landino see G. McNair, “Cristoforo Landino and Coluccio Salutat, on the Best Life”, Renaissance

Quarterly, Vol.47.No 4, [winter 1994]. [xxvii] Antonio Paolucci, “The Portraits of Titian”, Titian

Prince of Painters, (Venice: Marsilio Editori, 1990), 101 [xxviii] Bruce G. McNair, “Cristoforo Landino and Coluccio Salutat, on the Best

Life”, Renaissance Quarterly, Vol.47.No 4, [winter 1994], 744. [xxix] Oliver Logan, Culture

and Society in Venice 1470-1790, (New York: Scribner, 1972), 50. [xxx] Felix Gilbert, “Religion and the Thought of Gasparo Contarini”,

eds. Theodore K. Rabb and Jerrold E. Siegel, Action and Conviction in

Early Modern Europe, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 116. [xxxi] Vilmos Tatrai, “Portrait of Jacopo Contarini”, Treasures

of Venice, Paintings from the Museum of Fine Arts Budapest, (Minneapolis:

Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1995), 190. [xxxii] Rona Goffen, “Crossing the Alps: Portraiture in Renaissance Venice”, Renaissance Venice and the North, (New

York: Rizzoli, 1999), 116. [xxxiii] See Anton W.A. Boschloo and Gert Jan J. van der Sman, eds., Mandy Sikkens

tr., Italian Paintings from the Sixteenth Century in Dutch Public Collections, (Florence: Centro Di, 1993), esp. pp. 129, 132,133. [xxxiv] Late fifteenth century painting technique, especially Bellini see Peter Humfrey, Painting in Renaissance Venice, (New

Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 120. [xxxv] Peter Humfrey, Painting

in Renaissance Venice, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 113. [xxxvi] Lino Moretti, “Portraits”, eds. Jane Martineau and Charles Hope, The Genius of Venice 1500-1600, (New

York: Abrams, 1984), 32 [xxxvii] See Frederick Ilchman et el., Titian,

Tintoretto, Veronese Rivals in Renaissance Venice, (Boston: Museum of

Fine Arts, 2009). [xxxviii] Titian, Portrait of Girolamo

Fracastoro, c.1528, National Gallery, London. [xxxix] Luba Freedman, Titian’s

Portraits Through Arieto’s Lens, (University Park: Pennsylvania

State University Press, 1995), 12. [xl] Luba Freedman, Titian’s

Portraits Through Arieto’s Lens, 12. [xli] See Herold E. Wethey, The

Paintings of Titian, Complete Edition, Vol. II, Portraits, (London: Phaedon,

1971). [xlii] Carlo Ridolfi, eds. and trs. Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella, The Life of Titian,[1646], (University Park: Pennsylvania University Press,

1996), 126. Bibliography Biadene,

Susanna ed. Titian Prince of Painters, Venice:

Marsilio Editori, 1990. Boschloo, Anton W.A. and Gert Jan

J. van der Sman, tr. Mandy Sikkens. ItalianPaintings from the Sixteenth Century in Dutch Public Collections,Florence: Centro Di, 1993. Brown, David Alan et el. Bellini, Giorgione, Titian and the Renaissance of VenetianPainting,Washington, DC: National

Gallery of Art in association with New Haven: Yale Univ Press,

2006. Doerner, Max. The

Materials of the Artist and their use in Painting with Notes on theTechnique of the Old Masters,New York: Harcourt, 1934. Emile-Male, Gilberte. The Restorer’s

Handbook of Easel Painting, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1976. Ilchman, Frederick et. el. Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese Rivals

in Renaissance Venice. Boston: MFA Publications, 2009. Freedman, Luba. Titian’s Portraits Through Arieto’s Lens,University Park:

Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995. Goffen, Rona.

“Crossing the Alps: Portraiture in Renaissance Venice”, Renaissance Venice and the North,New York: Rizzoli, 1999. Humfrey, Peter. Painting in Renaissance Venice,New

Haven: YaleUniversity Press, 1995. Laurie, A.P. The

Technique of the Great Painters,London: Carroll and Nicholson, 1959. Logan, Oliver. Culture and Society in Venice 1470-1790,New

York: Scribner, 1972. Marijnissen, R.H. Paintings,

Genuine, Fraud, Fake, Modern methods of examining paintings, Brussels: Elsevier, 1985. Martineau, Jane and Charles Hope, eds. The Genius of

Venice 1500-1600, New York: Abrams, 1984. McNair, Bruce

G., “Cristoforo Landino and Coluccio Salutat, on the Best Life”,Renaissance Quarterly, Vol.47.No 4: [winter 1994]. Rabb, Theodore K. and Jerrold E. Siegel, eds. Action and Conviction

in Early Modern Europe, Princeton: Princeton University Press,

1969. Ridolfi, Carlo, eds. and trs. Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter

Bondanella. The Life of Titian, [1646],

University Park: Pennsylvania University Press, 1996 Rosand, David. Painting in Cinquecento Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, New Haven:

Yale Univ.Press, 1982. Tatrai, Vilmos. “Portrait of Jacopo Contarini”, Treasures of Venice, Paintings from the Museum of

Fine Arts Budapest, Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1995. Wethey, Herold E., The

Paintings of Titian, Complete Edition, Vol. II, Portraits,London: Phaedon, 1971.

|

Figure 2 and 3

Figure 2 and 3

Fugure 4. X-radiograph

Fugure 4. X-radiograph